- Home

- Sharon Pincott

Elephant Dawn Page 6

Elephant Dawn Read online

Page 6

Animals are still suffering from human-inflicted injuries all around me. I’ve already seen some of the most gruesome wounds imaginable, caused by snares. Ends of trunks ripped off, some barely long enough to reach the mouth with water. Bloodied flesh dangling on legs. A wire wrapped tightly under a chin, up past the ears, finishing in a disgusting bow of wire on top of the head. One W family member had his trunk severed to tusk length. He’d been cruelly stripped of his dexterity and didn’t survive.

Snares are a despicably cruel, cowardly way to kill an animal, and I’m dismayed by what I see, particularly since I’ve often been powerless to help. We’ve still only ever darted lone bull elephants. Darting those who are part of a protective family group is still considered too great a risk; there is fear that the other elephants will rush to the darted one’s aid, with ensuing danger to us. I keep finding females who are horribly injured but which none of the qualified darters are game to dart.

Over the course of a few tortured weeks I watch a little four-year-old calf from the V family, led by the adult female I’ve named Vee, debilitated by a tight wire embedded deep in his right back leg. He and his family have been drinking regularly at the same waterhole every day. They’re a small sub-family of only eight, with three adult females. They haven’t wandered far from this pan as the snared calf—as yet unnamed—is clearly unable to walk long distances.

But now Greg from the Painted Dog Conservation project has been thinking about a way to safely dart injured family members. His idea may be a little controversial, but I’m so thankful to have a way to at least try to help this injured V family calf. I’ve spent countless hours convincing Parks management to allow this darting to proceed. All of the red tape is more than irritating—indeed, it is infuriating. Everybody has their own agenda it seems to me, and it isn’t always the same as mine and Greg’s, which is simply to save this elephant. John tells me angrily that there are probably some people who just want to kill the calf and eat it. And there is indeed some tragic irony in us wanting to save it, when only a few kilometres away Parks staff are probably shooting one for rations. But we’re not about to let this deter us.

Finally, after obtaining the approval needed from Parks, there is an opportunity to test out Greg’s technique. There are lots of different elephant families around on this day; too many I fear, although I know that some will soon move off. From my daily observations, I know too that none have close ties to the V family. Through binoculars I find the snared calf. His horrific wound is getting worse by the day. He keeps his foot in the air and swings it backwards and forwards at every opportunity. It is awfully swollen and infected, and clearly very painful.

We thankfully now have access to a field radio network—my handset and base station kindly donated by that same Perth-based fundraising body, SAVE Foundation—so communication is simpler. Greg arrives with extra backup.

From the rear of an open 4x4 Greg takes aim with the first dart. It is a tranquiliser and it’s directed at Vee, the snared calf’s mother. She has a distinctive ‘v’ injury in her right ear and is easy to identify. Not one of the more habituated and better known Presidential Elephants, she could potentially cause us the biggest problem. The snared elephant is her youngest calf, still occasionally suckling, and she is likely to be particularly protective of him. There is little doubt, given the age of this calf, that she is also heavily pregnant, a condition sometimes surprisingly difficult to confirm for certain, since female elephants routinely appear huge around the belly. But I know that elephants typically give birth about every four years, so an advanced pregnancy is very likely.

Rather than bringing Vee completely down, Greg has decided that she will instead be tranquillised with a concoction of drugs so that she will continue to stand, albeit in a sedated state. The dart hits, and a pink-feathered needle protrudes from her rump. Shocked by the sting of the dart, she runs a few paces and then continues to move off slowly. More tranquilliser is needed. A second dart has already been prepared. It’s a perfect hit once again. Vee now has two pink-feathered darts protruding from her rump. She moves off further into the bush, while we do some bush-bashing to keep up with her. The family group move with her, the snared calf at her heels.

We wait. Although she’s clearly feeling the effects of the tranquilliser, a third dart is fired from ground level (with armed support standing by), just to be sure that she is properly sedated. Although she is vocalising, other family members thankfully remain a short distance away. Because she is on her feet, they do not rush to her aid. A big old bull comes to harass her, and us, but he soon moves off.

It’s time now to administer the immobilising drug to the calf. Greg fires once again and it’s another perfect hit. In no time at all, the calf is down.

It is a little disconcerting working on an injured calf with his mother standing just metres away, although everything continues to go smoothly. Armed rangers keep watch while Greg removes multiple strands of hideously thick twisted wire from deep in the calf’s leg. He then injects large amounts of antibiotics, while I continuously spray water on and under the calf’s exposed ear to keep him cool.

Working quickly, Greg administers the reversal drug to the calf. Then he walks up to Vee to remove the three pink darts from her rump and to administer her reversal, all on foot and by hand. This was definitely not in the original game plan. But this man is fearless. After a long deep snort, the calf scrambles to his feet and walks over to his mother’s side. She is starting to regain mobility.

We feel joy, relief, pride. We smile. We hug. I brush away a tear. In the air, there is that sweet smell of success. ‘I’m proud of you,’ one of Greg’s colleagues says to me, while giving me an extra big hug. Of course it is Greg who has saved this calf, but as always I do feel proud to have played a part.

Perhaps Greg had been lucky to get the three sedation darts into Vee without her running off. Perhaps we had been lucky too that she had not, while standing sedated, fallen over into a life-threatening position. There were moments when she leaned to one side, and then leaned heavily forwards. If she had fallen forwards onto her chest, she could have suffered severe respiratory distress. There is still plenty to learn.

I become concerned when the de-snared calf doesn’t stay with his still drowsy mother, instead walking off by himself into the bush. With the deep open wound on his leg, he is particularly vulnerable to lions. The other family members are by now nowhere in sight. I stay to watch over them until nightfall, the family still split.

Back at my rondavel I have a restless night’s sleep, wondering if the calf has eventually returned to the safety of his mother.

Early the next day, I search and wait. Finally I sight the family of eight drinking once again at the same pan. It is confirmation of success. They’re all back together and the calf is already putting more weight on his injured leg. They show no signs of agitation at my close presence, despite their recent ordeal. I whisper a quiet thank you.

Weeks pass, and although I search daily, I haven’t seen them again. I consider this to be a good sign, believing that the de-snared calf is no longer inhibiting the wanderings of his family, but I long to know for certain that he is still okay.

Then one evening I’m driving home after a full day in the field when I pass a small family in the bush by the roadside. I hit the brakes. Out of the corner of my eye I’d seen the big v notch in Vee’s ear. I reverse quickly, feeling anxious. But I needn’t have been worried. There they all are, all eight members of the family. The de-snared calf is by Vee’s side. His little leg has healed so well, and it is clear there will be no permanent injury.

I name this little V family calf Victory—because a glorious victory it was.

SOULS THAT SUFFER

2002

I try to learn some isiNdebele. I figure that I should know more than ndlovu (elephant), Mandlovu (mother elephant) and mombe (cow). Although I’m told that isiNdelebe is simple to learn in comparison to some African languages, I’m unconvinc

ed. I’m hopeless at all languages and this one is littered with incredibly complex clicks.

Numerous people try to teach me where to place my tongue, how it should be depressed and where it should touch inside my mouth, in order to make these sounds. ‘Seriously? This is just never going to happen for me,’ I decide defiantly after listening intently to one of several clicks. ‘It’s just impossible for me to make that sound. It’s like a cricket makes. And I’m not a cricket.’

I end up learning no more than a couple of the most basic words, all devoid of clicks: ‘Salibonani, linjani bangane’. I feel like I’m asking for a banana. What I’m actually saying is, ‘Hello, how are you friend?’ Which is about as accomplished as I’m going to get. I ‘excel’ with just one more word, ‘Yebo’ (Yes). At least that one I can handle.

‘Say something in your language,’ I’m asked.

‘But this is my language,’ I try to explain.

To redeem myself, I try out a few good Aussie phrases. ‘G’day mate,’ I say, which just makes everyone laugh. And then, ‘Fair dinkum,’ which has the same effect.

I tell my kind teachers that it’s time for me to leave now, that I need to get out into the bush and record the level of the pans. The dry season runs from April until November, so the last few months before the rain comes are a particularly harsh time for the wildlife and especially for the elephants, who drink large quantities of water.

‘Some pans,’ I say, ‘are already as dry as a dead dingo’s donger.’ I admit it’s not a phrase that I typically use, but it has the desired effect: I get another laugh. It’s easy enough for me to compare a dingo to a painted dog and, if that causes confusion, to a jackal, which these women more often catch a glimpse of. But when I get to ‘donger’, I decide it’s definitely time to leave. Interestingly, it is the word ‘dead’ that I should have immediately remembered would cause me a problem. It’s not a word commonly used here. Once when I was told that someone was ‘late’, I embarrassingly asked when they would arrive. I had absolutely no idea I was being advised that this person had died.

Expressions are indeed an interesting thing, as I find out when I meet Dinks’ friend Shaynie, another white Zimbabwean. Dinks has recently separated from her husband and is now sharing a flat with Shaynie in Bulawayo. They kind-heartedly offer me their couch to sleep on while I finish my supply shopping, a laborious task that I do every two months or so. As we laugh and chat, slapping at mosquitoes which buzz around us relentlessly, I can’t help but notice Shaynie putting an impressive dent in a packet of cigarettes, knocking back cheap white wine (interspersed with the occasional bottle of Coca-Cola), and uttering some remarkably colourful language. Who on earth is this person? I wonder to myself.

I learn that Shaynie lived through some pretty violent times in the years following Independence, when her family resided on a gold mine. In those years, I was working in the prime minister’s office in Canberra, my career already on fast-track with parties galore to attend, while Shaynie was across the ocean trying not to die. From 1982 to 1987, it’s estimated that no fewer than 20,000 Ndebele (and some say many more) were massacred, and tens of thousands more were brutalised unspeakably at the hands of the newly elected ZANU-PF government. This is how the Ruling Party, very soon after taking power, dealt with its only political opposition of the time, those based on the Hwange National Park side of the country. This horrendous period in Zimbabwe’s history became known as the Matabeleland Massacres (referred to as ‘Gukurahundi’ by the local people) and is now widely viewed as genocide: the Shona from the east systematically eliminating the Ndebele from the west. Caught up in all of this fear and bloodshed, there were periods when Shaynie had slept with a G3 rifle under her bed, and carried it with her everywhere she went. It was clearly an awful time.

I can’t help but laugh, though, when she tells me of one evening when she was about seventeen and feeling rattled after several recent murders at the mine. Everyone aside from Shaynie was a few hundred metres away at the mine’s club. Still carrying a rifle, she was lazing on the lounge-room couch watching Dallas on television as the saga of ‘Who shot JR?’ was unfolding. Getting to her feet at the end of the episode, she crazily tried to balance gun, cigarette, Coca-Cola bottle and a book in her hands.

‘In a flash the rifle hit the coffee table and there was an almighty crack. Hysterically thinking that I was once again under attack, I was racing frantically out of the door towards the security of the club, covered in white dust.’

As it turned out, she had shot the television! Its frame was still intact, but the glass had been reduced to tiny slivers, there was a hole in its rear, and an impressive crater in the white plaster of the wall, where the bullet had ultimately lodged. Predictably, the family joke became: ‘Who shot JR?’ . . . It was Shaynie!’

And this night in Bulawayo, gun-toting Shaynie becomes part of my Zimbabwean life. She’d previously been impressed when Dinks had spoken of her elephant friend (me), her hyena friend (Julia), and her froggie friend (Lol, who adores frogs). Now she has her own ‘animal friend’, and in time I become especially grateful for her presence in my life.

Months pass and Carol arrives from Harare, generously bringing with her mouth-watering goodies only available in the capital. I’m living primarily on instant noodles with sweet chilli sauce and tins of preserved fruit so it’s a treat to have something fresh and different to eat for a change. As a thank you, I take Carol out with me to meet some of the Presidential Elephants.

The gorgeous Wilma is a high-ranking member of the W family, a matriarch of one of the five W sub-families, just as Whole is. When I’m not calling her Wilma, I’m playfully calling her ‘that wicked woman’, given she has doused me with sand several times already while dust-bathing only a metre or two away from the open roof of my 4x4.

Wilma has unquestionably become another firm favourite of mine. On this day Carol and I stumble upon her just hours after she has given birth. She is still dripping blood and the tiny baby—a girl—is struggling to stay upright on wobbly legs. Carol names the baby Worry as this tiny one is very swollen where part of the umbilical cord is still attached, and walking strangely with a bulky lump hanging very low between her legs. I am indeed a little worried about her. She’s the first baby that I’ve seen on the actual day of its birth. But I hope for the best and look forward to monitoring her progress. I find myself hoping that I might be around to see her give birth to her own calf one day.

While new life is celebrated—and I, elated, start feeling like a proud grandmother to the newborns—human-inflicted injuries keep cropping up before my eyes, which then pull me into depths of despair. I so often feel like I’m on an endless roller-coaster ride of highs and lows, something that I’ve never had to deal with before.

Now, it’s one of Lady’s family who has been horrifically snared.

Louise is the mother of this latest snared elephant; a calf just two years old. Instead of cavorting like the others his age, he wanders around dejectedly, distressed and clearly in pain. His snared leg is a gruesome sight. It is the worst wound that I’ve seen to date, and it’s even more heartbreaking for me given that he is part of a family that I’ve come to know well. Swollen and infected from an excruciatingly tight wire, his little leg has literally burst, with raw bloodied flesh dangling hideously. The wire has snapped and is thankfully now off, but the aftermath is sickening.

I agonise over whether to request for him to be darted, in order to administer antibiotics. Everyone is still learning about the best way to dart within family groups. Would Lady, the matriarch, have to be darted as well as Louise, the mother? Darting always carries some risks for the elephants, and it seems wrong to risk too many other lives unless it is absolutely necessary. I observe his snare injury over several weeks, and then finally manage to get Greg onsite. It isn’t likely to make much difference, since the amounts are small, but Greg decides to take the opportunity to administer antibiotics in a series of non-barbed darts that will, by desig

n, fall from the young elephant’s hide once they automatically inject upon impact. Greg hopes these antibiotics might aid his recovery a little. It is evident from the calf’s horrific injury that it will be a long, long road to recovery.

I revise the name I’d previously given to Louise’s son, and now call him Limp—which is all that he can do.

One day soon afterwards, Louise is on her own in the bushes about 25 metres ahead of me. Limp is on my right, packing his little injured leg with sand in an attempt to get some relief. On my left I spot two lions, and I can taste the adrenalin. I hear in my mind the words often spoken by Parks staff: ‘Do not interfere; let nature take its course.’ I don’t interfere, but with my 4x4 motor running, I am ready to interfere. How many countless times has man already interfered, with rifles and snares? Limp’s injury is not nature’s doing. He’s surely been through enough, and to now get tackled by lions is simply too cruel. To my great relief, the lions show little interest and Limp eventually returns to the protection of his rumbling mother.

Days later I watch him take pleasure in a mud bath. He is having some fun. For the first time in a long time he’s enjoying being a baby elephant. He’s clearly feeling a little better but the moment is bittersweet.

I am so distressed by the sight of all of these snared, suffering elephants. Despite this heartache I can’t give up, for by now my soul is wrapped up in the endeavour to help save them. It’s a dream to be able to spend my days among elephants, but more and more often now this dream is fused with nightmares.

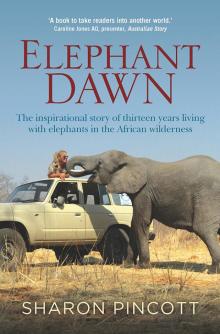

Elephant Dawn

Elephant Dawn