- Home

- Sharon Pincott

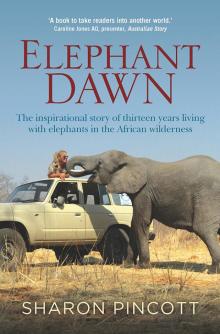

Elephant Dawn

Elephant Dawn Read online

‘A raw, honest story that needs to be heard. Sharon Pincott gives a passionate and moving voice to a species in peril; the silent, innocent victims of man’s greed.’

Tony Park, bestselling author of An Empty Coast

‘A woman on a passionate mission. Her astonishing adventure. Political intrigue. A book to take the reader into another world.’

Caroline Jones AO, presenter, Australian Story

‘This mesmerizing book is not just about a love of elephants, it is also about the indomitable spirit of someone who followed her passion. Sharon Pincott is one of the bravest women I have ever known. She has risked so much for elephants and it is a gift to us that we can now read this moving account of her thirteen years in Zimbabwe fighting to save a population of elephants she came to know intimately.’

Cynthia Moss, world-renowned elephant specialist,

celebrated in BBC’s Echo of the Elephants

First published in 2016

Copyright © Sharon Pincott 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 9781760290337

eISBN 9781952534089

Maps by Janet Hunt

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Australia

In memory of Lady

Some names in this book have been changed to protect identities.

CONTENTS

Prologue

Plain Crazy

Green Eggs and Ham

Is that a Duck or a Frog?

Elephant Rumbles

Cutting the Wire

Rhino Scars

Selling Up

No Looking Back

V for Victory

Souls that Suffer

In the Bush

Loopy

Honorary Elephant

A Million Miles from my Childhood

Giving Something Back

Christmas in the Mist

Into Another World

Carrying On

Skidding Sideways

Nothing Bad Lasts Forever

The Elephants will Speak to You

Will the Eagles Look Out for Me?

Enough to Pee Your Pants

How Long is the Fuel Queue?

On Friendly Land

Waiting for the Rains

The Letter

An Eagle in the Wind

Just Can’t Do It

Trying to Catch Dreams

Disorderly Conduct

Masakhe

Billions and Trillions

Pizza and Ice-cream

Finding Adwina

Mugabe’s Cavalcade

Grantham

Starting Anew

Meeting Cecil

An Elephant Kiss

Visitors

Becoming Britney Spears

Lady

Splitting Apart

Finding Tim Tams

Bulldog with a Bone

The Log with Teeth

A Fool’s Errand

The Litmus Test

Godspeed

Another Path

Postscript

Acknowledgements

‘The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.’

— Mahatma Gandhi

‘You have enemies? Good. That means you’ve stood up for something, sometime in your life.’

— Winston Churchill

PROLOGUE

I am sitting at a desk in a high-rise office block in Brisbane when an email arrives in my inbox. Contracted to Telstra as an information technology consultant, there is nothing unusual about this. Even my colleagues sitting only a few metres away send me emails with documents to review. I sigh under the weight of more apparent work and choose to delay the inevitable. How important can it be?

On this warm autumn day in the year 2000 I learn that my friend Andy Searle, a wildlife warden in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, is dead. He was 38. I am one year younger. He was alone, heading home to his wife, Lol, and young son, Drew, after a rhino tracking outing inside the national park when his helicopter went down.

Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe’s west is a place that I have come to know well. Now I’m travelling there unexpectedly for the funeral of my friend. Only last year, Andy and Lol had been my guests on Fraser Island, the world’s largest sand island off the coast of Queensland where I’d spent many childhood holidays. Fond memories of them holding hands, splashing through waves with seagulls flitting around them, brings tears to my eyes.

As I jet over the ocean, a deep rectangular hole is being dug in the earth by Andy’s friends, as is the African way. He will be buried at the edge of the vast 14,600 square kilometre tract of land that is the national park. For some it might seem a lonely place to be laid to rest, but not so for Andy. He will be at one with the wildlife that he dedicated his life to: creatures such as the rhino, lion, giraffe and zebra. And the magnificent elephant.

It was in a nearby area, during 1999, that Andy first introduced me to the Presidential Elephants of Zimbabwe. He had taken me with him on a lion-collaring exercise and we’d stopped off at a waterhole to observe the comings and goings of some of these wild elephants. Andy believed that I belonged in the African bush. But neither of us realised how profoundly these magnificent animals would become the centre of my life.

I am present at Andy’s funeral held under a clear blue sky, in attractive bush surroundings beside his grave. I am among friends. A week passes, just another week for some but a particularly sorrowful one for me. I decide that I need to visit the site where the crash occurred, to see it with my own eyes. We’re soon on our way, escorted by a National Parks scout, driving past enchanting wildflowers and trees, animals and waterholes. Then we are off the tourist roads and into the bush. As I step down from our vehicle I catch sight through the bushes of the helicopter on the ground, lying broken. I pick a handful of bright yellow wildflowers and place them where Andy’s body had been found. I speak to him. I feel close to him. I make a silent promise to return.

Two days before I fly back to Australia, we have a braai (as the locals call a barbeque) and a sing-along accompanied by guitar beside Andy’s grave. It’s time for me to say goodbye. We arrive to herds of antelope keeping Andy company. United once again in grief, we watch in silence as an elephant wanders by in the sunset. The John Denver song ‘Leaving on a Jet Plane’ that we later sing under a vivid full moon, holds real meaning; I have no idea when I’ll be back again. Words from Kuki Gallmann’s book I Dreamed of Africa come to mind, bringing some comfort:

They had loved him, shared in fun, mischief, adventures. Now they shared the same anguish . . . contemplating their memories and their loss. This experience would forever live with them, and make them grow, and make them better, wiser.

I fly back to Australia and never quite settle into my First World life again

.

A decade earlier, I’d been happily immersed in my career as an information technology executive, which peaked with my role as national director of information technology for Ernst & Young. I had loved my work with this accountancy giant, together with the memorable camaraderie and lasting friendships that accompanied it, happily putting in exceptionally long hours. But it was time for a change. In 1993 I resigned from this last permanent position that I would ever hold and, at the age of 31, I moved across the Tasman to Auckland and began a series of IT contracts, including an enduring one with Air New Zealand.

I enjoyed a high-flying life with a harbour-view apartment, luxury cars and frequent first-class trips around the globe for business and pleasure. Somewhat surprisingly, Africa—and most notably a fascination with its wildlife—began to feature prominently in my life. Its great expanses of wilderness, replete with stunning fauna and flora, had become my garden of Eden. After five years based in New Zealand, I’d found myself back in Australia, living in a beautiful suburban Brisbane home and enjoying the comforts of being mortgage free. I continued to travel to the wilds of Africa as often as I could in between IT contracts that financed this growing obsession.

A few months after Andy’s death, while still contracted to Telstra, I’m invited to join a leadership seminar in Victoria’s Dandenong Ranges. It’s all rather New Age. I’m in a room filled with IT professionals lying on the floor, surrounded by candles, relaxation music and soft voices. Feeling cosy and warm with duvets and pillows amid snowy mountainous surrounds, we listen for three days to a man telling stories. Every story has a message. It’s up to us to find that message, confront it, and if we choose to, incorporate its lessons into our personal and professional lives. These few days help me to realise what is really important in my life: to believe in my own abilities, to look out for my own welfare, to find a balance between my personal and professional lives and not to worry unduly about the small stuff. My time here helps me to accept the things I can’t change and to leave life’s unnecessary baggage behind.

It is here too that I learn about a survey carried out among a group of 95 year olds. If they could do it all again, these wise elders were asked, what would they do differently? They would take more risks. They would take more time for reflection. And they would leave a legacy.

I head off from this seminar, having grown in mind and spirit, enjoying the warmth of new friendships and feeling ready to move my life forwards in a totally different direction. It is not what Telstra was hoping for when it invited me along. This is the last time that I work in information technology. I throw caution to the wind, resolving to embark on an entirely new and impossibly different life.

In Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe? Who in their right mind would voluntarily go and live in Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe?

PLAIN CRAZY

2001

‘Tell me again why I’m learning to do this,’ I plead.

‘They’re killing white farmers over there, under the pretext of land reform,’ I’m told matter-of-factly. ‘It’s the wrong time for anybody white to be going to live in that crazy country. Learning how to at least handle a weapon is a good idea.’

So I spend the early months of 2001 undergoing weapons training in Brisbane. I do this only because caring friends insist that it is wise. My neighbour is a security guard and he enthusiastically accompanies me to an indoor firing range where my shooting prowess is soon evident. With a revolver in hand I am lethal. He stands beside me shouting streams of mock abuse, trying to intimidate, to undermine my concentration and determination as I scramble to reload and fire. He doesn’t succeed in unsettling me. In one swift movement I shoot my would-be attacker right between the eyes.

At the same time, my white Zimbabwean friend Val has me making phone calls to Australian government agencies in search of the necessary forms that she will need to complete in order to get herself and her son out of Zimbabwe. Hundreds of thousands of others are doing the same thing, diving into the diaspora away from the madness of their president and his regime. Yet here I am, excited at the prospect of going in the opposite direction. Maybe I’m dangerously naïve—or perhaps just plain crazy.

Certainly, others seem to know much more about Zimbabwe than I. Many, though, don’t seem to know anything about this country at all. ‘Zaire?’ my father questions. We are siting on the patio of the family home where I grew up, the third of his four daughters, in the sleepy country town of Grantham in Queensland’s Lockyer Valley.

‘No, no, Dad,’ I sigh. ‘Zimbabwe.’

I dig out an old school atlas and flick through the pages until I find a map of the African continent. I point to Zimbabwe, a landlocked country in the south-east, just above South Africa. It is, apparently, judging by the confused reactions of my family and friends, a rather insignificant country known only for its president. I start to call my future home ‘Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe’ so that they will all remember where I’ve gone. Even this doesn’t always help, I realise, after bumping into a couple who ask when I’ll be leaving for Zanzibar.

‘You’re mad going to Zululand,’ says my dad the next time I see him.

I roll my eyes. ‘Zimbabwe, Dad,’ I say again. ‘I’m going to live in Zimbabwe.’

My ticket is booked and I will be flying into the town of Victoria Falls, home to one of the seven natural wonders of the world. The falls are flanked by the southern African nations of Zimbabwe and Zambia, on the Zambezi River. I dare not tell too many people this. More ‘Z’ words would only serve to confuse them further.

I haven’t yet decided whether I will sell my Brisbane home, or rent it out. For now I will leave it locked up, with kind friends happy to keep an eye on things and tend to my garden. I still have to plough through the messy web of visa approvals and paperwork needed to allow me to legally stay in Zimbabwe on a full-time basis. I leave everything as it is, packing just one suitcase, while remembering a promise I once made. Someone very close to my heart will accompany me on this journey—my nearly eighteen-year-old white toy poodle, Chloe, who took her last breaths just six months ago. She will travel with me in her little ceramic pot, and I will sprinkle her ashes in this country that I am soon to call home. For years I had promised her that, one day, she would come with me to Africa.

On 5 March 2001, 364 days after receiving that heartbreaking email, I gaze down on what looks like smoke, but is in fact the thick misty spray of the Victoria Falls. I disembark at a quiet, ramshackle airport in Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe. Flight arrival and departure information is scrawled in white chalk on blackboards, and immigration agents with rubber stamps sit behind rickety wooden desks like school children. There is not a computer in sight.

I breathe deeply. This is exactly where I want to be. It’s not that I’m worn out by my First World life. It’s simply that I believe I can make a bigger difference here.

There are few tourists arriving these days, a sign that international travellers are prudently heeding travel warnings to stay away. As I collect my bag from a line of luggage neatly assembled on the floor, I can see the beaming faces of Val and others as they smile at me through a gap in the wall, waving frantically. They’re my African family. We’re already bonded by a common choice of life in the African bush and an acute awareness of sharing this privilege with each other.

‘You made it,’ Val gushes as she hugs me tightly. ‘Your cottage renovations are just about complete, but first let’s go for lunch and a celebratory drink in town.’

We stop to marvel briefly at the falls, and to listen to the continuous thundering roar of the huge volumes of water plunging over its cliffs, appreciating its African name ‘Mosi-oa-Tunya’ (‘the smoke that thunders’). Vervet monkeys with powder-blue balls bound around in the treetops. At a safari lodge looking out over the spectacular Zambezi National Park we spot magnificent elephants, and excitedly raise our glasses in a toast.

‘Cheers!’ we all grin, clinking our glasses together and savouring this new beginn

ing.

GREEN EGGS AND HAM

2001

When I was just 24 years old I worked as an instructor for Wang Australia. Power-dressed to disguise my young age, I tutored executives and veteran secretaries in computer literacy and word processing, way back when most of the world knew little about either. My trainees were not always enthusiastic. In desperation, I turned to one of Dr Seuss’ legendary children’s books in an attempt to persuade them to try something new and different. I began each class—‘I am Sam, Sam I am . . . Do you like Green Eggs and Ham?’ But not even I imagined that my own ‘new and different’, some fifteen years later, would turn out to be quite so out of the ordinary. I’ve ditched it all and stepped outside my routine life. I’m about to start working with wild free-roaming elephants!

I saw my first wild elephant in South Africa’s Kruger National Park in 1993. I was instantly enthralled: his sheer size and magnificence took my breath away. Now I’m about to start up my very own project, working with the Presidential Elephants of Zimbabwe.

They’re a group of several hundred elephants who roam on a 140 square kilometre slice of land just outside the Main Camp entrance to Hwange National Park. This land is known locally as the Hwange Estate. Their special status was bestowed back in 1990, when a white Zimbabwean safari operator, who had close ties to the Ruling Party and an exclusive grip on this land, requested from President Mugabe a ‘special protection decree’ for the elephants that spend the majority of their time here. They were never to be hunted or culled and were supposed to symbolise Zimbabwe’s commitment to responsible wildlife management. President Mugabe issued the decree, and that’s how they acquired their name. Up until the year 2000, when farm invasions started and Zimbabwe began its downward spiral into violence, lawlessness and economic collapse, this name had no particularly negative connotations for most people. President Robert Mugabe was considered to be a liberation hero for his part in ending white rule a decade earlier.

Elephant Dawn

Elephant Dawn