- Home

- Sharon Pincott

Elephant Dawn Page 4

Elephant Dawn Read online

Page 4

He knew that two lion cubs were missing from their radio-collared mother, a collar that he had fitted: he’d seen the mother with only two of her four cubs just the day before. When two lone cubs unexpectedly appeared right in front of us, Andy immediately pieced the puzzle together. The cubs were weak and clearly wouldn’t survive for much longer without their mother, whom he knew to be several kilometres away. He made an on-the-spot decision to capture both of them, by hand.

‘Hold this,’ Andy said as he walked towards me, casually carrying one of the lion cubs by the scruff of its neck.

‘Hold that? Seriously?’ I muttered in disbelief. ‘Well, okay . . . ’ I grabbed the cub in the same way.

And so it was that on this day when we were all simply enjoying the splendour of Hwange National Park, I suddenly found myself in the back of our 4x4, holding a truly wild lion cub. These cubs were not sedated. They were not sleeping. They were alert and feisty, although thin and vulnerable. We held on to them as one might battle with a strange, overgrown domestic cat. I tried to memorise their every detail—their whiskers, their almond-shaped eyes and the colouring of their tails.

It was an extraordinary drive across the plains towards their mother. We finally caught up with her as the sun began to set. She clearly sensed we had lions on board, well before we had stopped and dropped them to the ground. After some tense moments while we wondered together whether they really were her cubs, we shared overwhelming joy to see them reunited. The lioness instinctively took the weakest cub in her mouth while the other one ran by her side. They all headed away to rejoin her other two cubs, who were watching from the safety of a fallen tree.

There had been no time to tag the rescued cubs, in order to easily identify them later. Everything had happened so quickly and night would soon be upon us. I had pleaded with Andy earlier to let me take a photograph, but he quite justly would not compromise our safety. They were lions after all, with full-grown relatives, and we were in their territory. And with just a flat tray, there were no ‘bite me barriers’ on the back of our 4x4!

In emails after I was back in Australia, Andy referred to these cubs as my cubs. He continued to give me updates on their wellbeing, right up until he died and their identity was lost with him.

‘I wish I had been there,’ was all that John could ever say.

There is another story that is often retold, and this time John was there as a witness. It was a rhino relocation that didn’t go quite as expected. It went perfectly well for the rhino, I suppose. It just didn’t go quite so well for me.

Andy was in charge of this operation and had granted me permission to stand close by, alone at the base of an Acacia erioloba, so that I could photograph the release of a radio-collared rhino. He was already up in the helicopter, all set to monitor where the rhino wandered. His men were on the ground preparing to release this great horned creature.

I knew that when the door of the transportation crate was opened, the rhino would be free to run off in any direction. I watched him back out slowly and for a few moments he moved only his head, taking in his new surroundings. I stood admiring his ancient splendour, wondering how anyone could slaughter such a magnificent beast for its horn.

Then, as luck would have it, the rhino turned and charged. Straight towards me.

‘Oh, give me a break,’ I remember thinking. ‘You could have run in any direction.’

I wasn’t about to miss this opportunity though. I snapped a photograph of him in mid-stride, thundering straight towards me. Then I found myself scrambling for my life up the acacia tree. Long, sharp, white thorns ripped my arms before I managed to reach a safe height.

Trying desperately to keep hold of my camera—I wasn’t about to lose that photograph now—I gazed down from my precarious position to the rhino below, his huge horn not far beneath my feet.

‘Don’t move! Don’t move!’ one of the National Parks scouts yelled at me, while everyone looked on helplessly.

Don’t move? Look at me! Where could I possibly move to?

Luckily for me, but not so for them, a group of spectators momentarily grabbed the rhino’s attention. After scattering them, he disappeared into the bush and I was free to climb down from the tree, a little shaken and nursing my bleeding ‘rhino scars’, which I was secretly rather proud of. When I looked up into the tree I wondered how on earth I’d actually got up there.

‘Do you still have your rhino scars?’ John asks me, whenever we reminisce.

Now, I sit quietly, staring into the flames of the campfire, wondering, If both Val and John leave, will I have what it takes to remain in the Hwange bush? Even my hyena friend Julia and her team-mate Marion seem unsure how long they might stay. If they leave, I’ll have nobody to catch a chicken bus with; those old, noisy and smelly, cramped buses that hurtle along like crabs, with their rear frequently hanging out to one side. Or nobody to hitchhike with, like the time we managed a lift to Bulawayo in a passing hearse.

We refill our glasses with Amarula. This is a delicious South African cream liqueur made with the tasty fruits of the marula tree, which elephants love to eat, that we love to drink. And we toast absent friends.

SELLING UP

2001

It’s another glorious dawn in the African bush. Val’s two-year-old son, Declan, appears at my cottage door and grabs me by the hand.

‘Sharon, come! Come! I want to show you what the ndlovus did to the garden. They’re in biiiigggg trouble!’ this little white boy declares with tangible urgency, his eyes wide. An ndlovu is an elephant; words from the isiNdebele language—the native tongue of the local Ndebele people, who live in this province called Matabeleland—frequently pepper Declan’s sentences.

I’m still rubbing sleep from my eyes as he yanks me out of my cottage and hurries me towards the lodge garden. I soon see that the ndlovus really are in big trouble. What was once tall, thick, green plant-life has been sheared off at ground level. There are a few—really rather large—craters where the roots were savoured too. Then, to rub salt into the wound, the ndlovus quenched their thirst in the swimming pool. Any guests so inclined would have to swim with huge clumps of dirt and floating banana tree roots.

‘Please, can’t you keep “your” elephants on a leash?’ Val asks me wickedly. We can do little but laugh, and then clean up the mess.

Even Declan now knows me by the isiNdebele name ‘Mandlovu’—meaning ‘Mother Elephant’—given to me by Gladys, one of Val’s staff members. Gladys had first christened me ‘Thandeka’, meaning much-loved. Being known as Thandeka Mandlovu—much-loved Mother Elephant—is an honour that I’m thrilled to accept. Beautiful wooden signs have been skilfully hand-carved by one of the safari guides, featuring elephants and my given name, to recognise this special tribute. Everywhere I go now, and despite the colour of my skin, the Ndebele people call me Mandlo, the shortened version. Even John is busy hand-tooling an exquisite leather book cover for me, featuring elephants and my isiNdebele name, as a special keepsake.

So when terrorists attack the United States on September 11—six months after my arrival in Zimbabwe—I’m jolted back to a reality that I have been avoiding. While deep in the bush, I feel strangely removed from this appalling tragedy while simultaneously overwhelmed by grief at the horror of it all. The events taking place around the world are shocking. Even so, some of us, I believe now more than ever before, need to stay focused on the welfare of the wildlife, particularly in troubled and seemingly insignificant places like Zimbabwe. It is a country fortunate to still have such a diverse variety of life, but for how much longer, I wonder?

I’m frequently asked, ‘Why do you bother with the wildlife, in a country where so many people are suffering?’ My answer is always the same. I try to explain that there are hordes of organisations worldwide assisting hungry and disadvantaged people. ‘It doesn’t mean that I don’t care about the underprivileged people,’ I say, ‘but there’s relatively few organisations assisting the wildlife—and even fewer bo

thering in Zimbabwe.’ I emphasise that I’m one lone person who needs to focus my energy where I believe I can make the most difference. And this happens to be with the wildlife, and with a very vulnerable species. The elephants are key to attracting much-needed tourist revenue, which is crucial to this country’s economy. And having compassion for another species is really what humanity is all about anyway.

A disturbing incident that I recently witnessed inside Hwange National Park, after it closed to tourists for the day, doesn’t help tourist revenue, the economy, or indeed anything at all. It left me alarmed and with the impression that some people employed here are little more than poachers themselves. Just a short distance up the road from where I sat with colleagues on the tourists’ favourite Nyamandlovu platform (a wildlife viewing structure not far from the main gate), Parks staff drove by and casually shot at wildebeest right beside us. Naturally the next morning, after all this commotion, there wasn’t an animal in sight for tourists to see, let alone any wildebeest, which are certainly not abundant in this area. Nobody publicly questioned this authorised ‘ration hunting’ (which is hunting to feed Parks staff), since that would mean risking permits. That Parks staff would ration-hunt wildlife at all baffled me; that they would do it right in the middle of key tourist areas, inside a national park, was simply unfathomable. Needless to say, John and others are horrified. We all know that elephants are also ration-hunted frequently. There has to be a way, we want to believe, to positively influence attitudes and policies.

In the wake of the awfulness of September 11, I decide that I will sell my Brisbane home, even though my visa situation is still not sorted out. And I will stay on with the elephants, no matter what, and make a real go of things.

Having already spent the maximum time allowed in Zimbabwe on a tourist visa in one year, and also because I need to start to think more about my house sale, I am returning to Brisbane for just a few weeks. This is the city where Val is planning to live—simply because it’s where I’m from. In fact we’ve discussed the possibility of her renting my home, but it’s clear to me that in order to fulfil my commitment to stay with the elephants, I must sell up, since I’ll need this money free to support my work.

Soon after stepping off the plane I experience a very real culture shock, even though I’ve been away for only six months. It feels surprisingly odd returning to the Western world. There is a regular supply of electricity and water, and there are working telephones, fax machines and photocopiers. There are no fuel queues; no streams of people ‘footing’ along the roadside; no one constantly thrusting carvings and bananas under your nose. People look familiar, yet these are faces I do not know. It takes me some time to figure out that this feeling of familiarity among strangers is because I’m once again in the midst of a sea of white faces. There seems to be an incredible number of food and clothing shops, offering endless varieties of brands and styles. My own walk-in wardrobe is overflowing with clothes. Why had I ever thought that I needed so much clothing? Everywhere, there is so much ‘stuff’. I walk around a little bewildered, it all seeming to me now more than a tad excessive.

Even though the materialistic world in which I’d previously lived is glaringly obvious to me now, it is still a little overwhelming to think about selling and packing up my life completely. But regardless of what the future holds, I know, with a comforting certainty, that I could never live quite like this again. Despite it once being an all-consuming and rewarding part of my life, I can’t pretend to miss my former career and the lifestyle that had come with it. There have certainly been times in this past year when I’ve craved a more functional country and a five-star meal. But, despite everything, there is now no place in the world other than Hwange that I want to be.

I believe my decision to sell up is the right one. I make a promise to myself that if the time comes when I ask myself, ‘You have six months to live and can do anything you wish with your remaining time on earth. Where will you spend your time?’ and my answer is no longer ‘With the elephants in Hwange’, then I will leave Zimbabwe. It will be my reality check, my litmus test.

I make sure that my friends in Brisbane are happy to keep an eye on things for a couple of months longer, and decide that I’ll return to Australia again in early 2002 to pack and sell up.

I fly back to Zimbabwe, happy that there are still no computers in sight at the airports. Like countless others in past years, I have no desire to pay the substantial bribe that would be necessary to facilitate my re-entry while my visa situation is being sorted out, and so I present a new passport. There is no visual evidence that I’ve already been here for six months this year. I breathe a sigh of relief when I hear the thump of the officer’s stamp on its blank pages. I do not lie when I tell him that I’m on my way to Hwange, to see elephants.

It’s wonderful to be back, and I immediately drive myself into the bush to try to find some elephant families. It’s always like a box of chocolates in the field; I never quite know what I’m going to get. Thankfully, I don’t get a flat tyre. The sights, sounds and smells of the Hwange bush hit me once again, squarely in the face, and I know that I am back where I belong. Others, however, don’t feel quite the same way about their own situation.

When Val starts to speak with more certainty about her planned move to Brisbane, I am silent. John says, ‘I want to come with you.’ And I notice others consciously stopping themselves from blurting out, ‘Me too.’

I have returned to Zimbabwe with thousands more elephant photographs developed in Oz. For the next few months, I work long into the night, looking closely at left ears and right ears, tusk formations and family group configurations, excitedly watching my identification booklets take shape. It is so satisfying, trying to figure this all out. Every day by 10 a.m. I’m out among the elephants, right through until the sun sets.

My three sisters and I grew up helping out on our parents’ farm in Grantham: catching and throwing cabbages in a chain between cutter and packer, washing cucumbers, picking potatoes, mowing lawns. We were rarely idle. After schoolwork was complete, paint-brushes, brooms, rakes and mops were frequently thrust into our hands. My mum has a serious aversion to idle bodies. I was also granted the freedom to roam and the independence to indulge my curiosity for nature. My impressionable childhood days were not filled with loafing around. I’m more than happy to burn the midnight oil. As I learn more and more about the elephant families, they occupy an increasingly special place in my heart. The days fly by.

Soon, it’s Christmas. And sadly, Val is gone. Although not my original plan, I’ll be finding myself a new place to live. It’s more than I can think about for now, though, and I join Julia and our mutual friend, Dinks, inside the national park for an early bush Christmas. Dinks was also a friend of Andy and Lol and once managed the Hwange Main Camp restaurant. She now lives in Bulawayo. I’ve already known her for several years and love her ‘to the moon and back’, as we so often say.

It’s Mother Nature entwined with Father Christmas. Nothing beats celebrating the festive season in the African bush. We hang decorations (discarded porcupine quills, seed pods, feathers) on a broken branch of a tree, which we push into the soft earth. From the paper plates on our laps red-hatted koalas and kangaroos smile back at us.

Julia always has some memorable plan up her sleeve. Her Christmas gift to us on this day is a beauty salon in the bush, accompanied by a glass of chilled wine. With grotesquely bright masks on our faces, and our feet soaking in red plastic basins, we revel in the throaty rumbles of passing elephants. When an afternoon thunderstorm forces us to scurry across the sandy ground to shelter, we laugh and laugh, knowing just how crazy we all must look. We are alone though, except for the elephants. For now, it’s still easy enough to forget that the country is crumbling around us and that people everywhere continue to flee.

I fly out once again to Australia, and sell my beautiful home.

NO LOOKING BACK

2002

‘Mushi hat,’ John mut

ters in thanks on my return, when I present him with his very own Akubra, the legendary hat of the Australian outback. It is indeed a really nice hat. I may have chosen to live elsewhere, but my national pride and the symbols of my origin don’t vanish, such as a jar of Vegemite I’ve squirrelled away to savour alone (here South African Marmite is preferred), and the packets of delectable Tim Tams (my favourite Aussie biscuits) that I will grudgingly share.

It took me more than three months to sell my Brisbane home, my car and a considerable portion of my belongings, and to store the rest. I had to dig deep to find the courage I needed to go through with it all. The most difficult time had been the lead-up to my decision to sell. Once I’d reached that decision, it all became easier, although I knew that I was leaping into just another level of the great unknown. A little apprehensively, I’d walked around the empty house that was no longer mine: the lush garden, the sparkling pool, and then from room to room switching off the lights. I’d gently closed the front door behind me and, without looking back, driven away from my past life.

My visa problems are finally sorted out, at least for now, and I have re-entered my homeland of choice on a two-year work permit, required despite my efforts being purely voluntary and self-funded. I dismiss suggestions that I should instead find a Zimbabwean to marry. This alternative holds no appeal for me at all. I was married—for what felt like about five minutes—when I was in my twenties and it’s not something that I’m keen to do again, despite having been assured that I would be worth many mombes (isiNdebele for cattle).

‘How many mombes?’ I want to know.

Cattle are highly valued here as a display of prosperity. Some locals clearly hold me in high esteem and estimate my bride price to be 20 mombes! But whether it’s 20 or only one or two, I feel quite certain that my mum and dad in Australia—the would-be parents of the bride—can do without them.

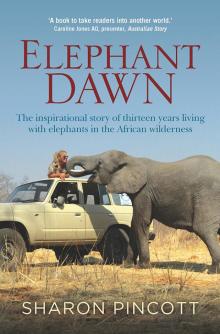

Elephant Dawn

Elephant Dawn