- Home

- Sharon Pincott

Elephant Dawn Page 17

Elephant Dawn Read online

Page 17

Out in the field, I attempt to get my records up to date with births, deaths and disappearances, which is a task that is ongoing. All families by now hold a special place in my heart, but some remain firm favourites. Lady’s family always react immediately when I call to them, trunks swinging rhythmically as they hurry my way.

Little Libby is growing up fast. Ever the playful clown, she uses her mother’s thick legs as poles to scratch her backside on. The sight of Loopy always brings a sense of pride, in the knowledge that we saved him from certain death. Limp’s snared leg is finally starting to properly heal, three long years after his injury. It’s exciting to watch Lady’s adult daughter, Lesley, become increasingly mellow; she’s soon to give birth for the very first time. She leans her trunk against my side window, standing just centimetres away with her eyes closed. Soon, all five adult females will be nurturing babies under twelve months old, making it a particularly beautiful period to spend time with them. Louise places her trunk on the back of Lazareth, son of Lucky, who leans against Libby, who is suckling from Lady. Lee swirls his trunk around and around and around. Litchis and Laurie lie down on their sides in the sand. Lady’s sister, Leanne, welcomes my hand on her tusk. Lucy, Levi, Lindsay, Lol, and Leroy are around me too. I feel like the most privileged person in the world; an honorary member of this family. It’s sad that I spend time wondering who their third snare victim will be.

There’s never time, these days, to hang out with a family for too long. The list of daily demands is staggering. There are snares set right beside lodges; animals falling into lodge sewerage pits; rubbish pits not properly maintained attracting wildlife to what certainly should not be eaten; fallen electricity cables that could easily electrocute giraffes and elephants; cement drinking troughs carelessly dug out too deeply so that they trap baby elephants; more snares; more elephant carcasses. As the exodus from the country continues, the capabilities and energy levels of some of those who remain, here in the bush at least, is deeply concerning. So much is not properly done or not done at all without prompting.

Now in October temperatures soar above 40 degrees Celsius, day after day, the heavy, thick air making it difficult to take a deep breath. Feeling dejected by it all, I find myself sitting on the parched ground, head on my knees. Flat tyres in the sweltering heat don’t help.

‘No wonder they call this suicide month,’ I groan.

I look once again at Kanondo pan and feel a sense of desperation over the neglect. There have been changes in lodge management during the land grab madness, and those now in charge don’t seem able to grasp what needs to be done. The neglect during the land grab period worsened everything. This key pan is not only dry, it’s full of weed-covered silt. It must surely rain soon, and then it’ll be too late to clean out and deepen this important pan, using a mechanical scoop, to improve its water-holding capacity. Tired of waiting for those responsible to act, I jump into action. It simply needs to be done, and done now. I speak to my neighbour, Morgan, who works for the Painted Dog project, about borrowing a tractor and scoop that might do the job, and negotiate a deal to secure a skilled operator. With a few phone calls, I manage to get diesel donated. Within just a couple of hours, we are set to go.

The scorching heat of the day is relieved somewhat by puffy white clouds intermittently hiding the sun. Sables, waterbucks and kudus look on hopefully as the scooping begins. It is a long and noisy process. Much of the pan is deceptively still damp beneath the layers of crumbly dry soil, threatening to bog down the 4x4 tractor—which unfortunately has the scoop attached behind it, forcing the tractor to go in head-first. The men, working through the blazing heat, do what they can, carting load after load of silt out of the pan, dumping it far enough away so that it won’t wash back in. Soon though, the tractor is hopelessly bogged.

‘Can’t you get your friends to assist, Mandlo?’ Morgan asks.

It takes me a moment to understand his meaning. I follow his gaze, focused a few hundred metres away on my big grey friends.

‘They could pull us out easily,’ Morgan declares. ‘Can’t you get them to help?’

Unfortunately, it isn’t quite that easy.

On Day 2, as I stand overseeing this scooping, I realise that the job is much too big for the equipment being used, and I realise, too, that at this rate we will never finish before the rains arrive. I’m also aware that the tractor and scoop will soon need to be returned to the Painted Dog project. I need to prioritise. I select just the outer rim of the pan for the men to concentrate on, so that at least this smaller section will be complete and ready to capture decent rainwater.

When thunder rumbles three days later and more powerful equipment has still not been secured to finish the scooping, I finally admit defeat. We’ve done our best. The pan is in better shape than it had been, but plenty more could have been done if those responsible had tried to secure more powerful front-end equipment.

This pan will no longer hold the quantity of water that it did in past years. There is little more that I can do though. I have nagged enough. Now, the rain can fall.

As the year wanes I eagerly await the full moon, for it’s said that with it comes a change in the weather. The night of the October full moon turns out to be practically cloudless. I search the night sky for a hint of rain, but there is none. Most of the Presidential Elephants are forced to move elsewhere since the estate pans now hold more mud than water. The adults in Lady’s family have learnt to use their trunks to skim the surface of shallow water, in order to get a clean mouthful. Their youngsters are learning this skilled behaviour too, but they’re struggling. It’s heartbreaking to watch such despair.

At long last, on an early November evening, while an unknown elephant bull attempts to demolish the coral creeper in my garden, cracks of thunder split the silence. For a short while, rain pelts my thatched roof. I lie on my sofa bed on the floor of my rondavel, with lines from Bambi from my childhood racing through my mind. Rather than Bambi asking, ‘What’s all this white stuff?’ I imagine little Libby out there in the darkness asking her mother in a wee voice, ‘What’s all this wet stuff?’

‘Why, it’s rain!’ I hear Lady saying.

‘Rain?’ little Libby questions innocently, never having felt anything like it before on her young body.

‘Yes,’ says Lady, ‘the rains have finally come.’

And so, mercifully, I can stop willing it to happen: the drought is broken at last.

As Christmas approaches, I gaze out from my rondavel at all the mistletoe in the rain trees. These large clumps of greenery drooping from high boughs appear to favour this type of tree, so named because of the clear liquid secreted by a spittle bug that falls from it like rain.

‘Mistletoe is a symbol of love and peace,’ my friend Miriam tells me from Harare. ‘Long ago it was decreed that those who pass beneath it should kiss, to proclaim the strength of love; to seal a friendship.’

Perhaps that’s why I find myself so drawn to it, not just at Christmas time, but throughout the year. Only now do I understand that it signifies my relentless longing for peace and tranquillity in this, the animals’ world. It’s a longing that never seems to be fulfilled.

THE LETTER

2006

The Swahili-speaking people in Kenya have a saying: ‘Wapiganapo tembo nyasi huumia’ (‘When elephants tussle, the grass gets hurt’). For me the meaning is already very real: ‘When officials wield their power, innocent people get hurt.’

I’ve been living in Hwange among elephants for almost five years now, the most tumultuous five years of my life.

The ex-governor’s family have realised that the Parks Authority really won’t be issuing them a sport-hunting quota for this year, for the vlei land that they claimed as their own, and they are seething. A story in the Bulawayo government-controlled newspaper, The Chronicle, quotes the brother-in-law as saying, ‘That Sharon Pincott is bad news and until we deal with that woman once and for all, we will always have problems. She is d

estroying the whole conservation.’

The words ‘once and for all’ have only one meaning in Zimbabwe.

These never-ending threats and attempts at intimidation are so draining, although I’m actually pleased that this is at least now in print for the world to see. When I complain to authorities in Harare about this threat on my life, the story quickly disappears from the newspaper’s website.

Taking advantage of his new ministerial position, the ex-governor writes me a three-page letter. The letterhead reads ‘Khanondo [sic] Safaris & Tours’. He’s misspelled the name Kanondo and clearly hasn’t bothered to change the company name after their eviction. He formally accuses me of being a spy, writing that I am ‘an agent of the Australian Government assigned with the task of frustrating [Zimbabwe’s] land reform programme’.

They hang spies in countries like this! It’s a desperate, laughable allegation and yet another attempt to scare me into leaving the country—or to get me expelled.

Why is this little Aussie girl from Grantham in country Queensland considered such a threat to this man, who calls himself Mugabe’s ‘obedient servant’ and is fast becoming one of the richest men in the country? I suppose I should be terrified, but I am simply dumbfounded at the crudeness of it all. There’s not one person in the Australian government—apart from the Australian ambassador in Harare, with whom I’ve made contact for my own peace of mind—who would have any reason to know that I even exist.

The ex-governor refers to me as ‘an Australian reject’, calls me ‘illiterate’, and states that my ‘provocation deserves to be stopped one way or the other’. ‘It is common knowledge,’ he writes, ‘to all patriotic Zimbabweans that you were sent to this country to frustrate the land reform programme especially in Matabelaland [sic] North Province where you were to work with the opposition in this diabolic act. Your mission totally failed as I frustrated it during my term as governor hence your anger.’

These are the desperate words of a very desperate man.

My activities in Zimbabwe are ‘nefarious’, the ex-governor writes. It’s a word I’ve never heard before. ‘Evil, despicable’, my thesaurus clarifies. Well, at least that might explain how he knows it, I think to myself.

He further claims that he ‘voluntarily moved out from [the Hwange] estate after realizing the area was infested with anti-land reform agents like you . . . Never was there a request or order from anybody for me to leave the area serve [sic] for your lunatic and imaginary eviction, which only exists in your mind and that of your informers . . . I am clear in my mind that you are nothing but an Agent of the Australian Government assigned with the task of frustrating the land reform programme when most racist white Rhodesians started running away from this country to Australia . . . The truth will soon be told about you and your local corrupt accomplices.’

He accuses me of having ‘sent reports to your country Australia demonizing this country and its leadership’ and goes on to say ‘your country is totally Anti-Our President and its leadership and continues this demonization of him on a daily basis using false information from its spies and agents like you.’

Demonise. Demonisation. Demonic. Satanic. These words are often used in Zimbabwe’s government press, particularly to describe the Opposition party.

The letter concludes: ‘I think its [sic] high time you cautioned your handlers that soon and very soon you will be working for the Australian Kangaroo Conservation Project’, and is signed and dated 23 January 2006.

The President’s Office has been copied into this letter, as well as the three Cabinet ministers I had previously visited in Harare.

What this man hasn’t banked on, is that unlike the vast majority of people in Zimbabwe right now, I won’t allow myself to be bullied. I immediately fax this letter to all of the people listed as copied in. I’m hardly surprised when I learn that none of them have in fact received a copy of it.

I can’t decide if I’m frightened or pissed off. The locals are scared for my life. They know what would happen to them, if they were in my position: ‘accidents’, beatings, rape, disappearances, murder, and not only of them but of their families too. Being a foreigner affords me just a little extra protection and these thugs are forced to be a little more restrained than usual.

‘But are any of us really that stupid?’ a friend declares after reading the letter. ‘Does he think we fell off a paw paw tree? They are just trying not to lose face.’

‘This is the quality of the men running our country,’ says another. ‘It is an embarrassment to our race.’

Shaynie simply says: ‘Sharon, get the hell out of there.’

Shortly after receiving ‘the spy letter’, as it becomes known, I spend a pre-arranged month in Australia and New Zealand visiting family and friends. It’s almost two years again since I’ve been Down Under. I’m one of the lucky ones, able to leave Zimbabwe whenever I wish. Many of my friends, restricted by no spare money and tough visa requirements when travelling on a Zimbabwean passport, are not so fortunate.

On my departure, a customs officer asks me if I’m carrying any Zimbabwean dollars, as it has become illegal to take more than the equivalent of a few US dollars out of the country.

‘Why would I want to take Zimbabwean dollars out of the country?’ I retort, bewildered. ‘I couldn’t even give them away if I wanted to. They’re worth almost nothing in this country, and they’re worth absolutely nothing in every other country.’

I can tell that he’s heard it all before, no doubt millions of times. I know that he is only doing what he’s been instructed to do, regardless of whether he agrees with it or not.

Onboard my Qantas flight out of South Africa, ‘I Still Call Australia Home’ streams into my earphones, and I feel tears sting my eyes. This song manages to pull at my heart-strings every time I hear it. The truth is that I’m more confused than ever about where home is. But I still feel that it’s the wild spaces of Zimbabwe, and the elephants, that hold my heart—even though it sometimes feels and sounds like hell on earth. I am relieved, though, to be about to spend time in a safe, sane, functional country, at least for a while.

With my family, I feast on a much longed-for seafood smorgasbord in Toowoomba, and I eat chocolate and more chocolate, and share excellent red wine and cheese with my dad. I allow myself to enjoy the comforts of First World life. I also visit Eileen, Andrea and Bobby in Auckland and delight in the sight of the sea; endless vistas of crystal clear water. Eileen and I sit on a bench in an open-air restaurant built over the sparkling ocean, devouring delicious, melt-in-your-mouth calamari, and chips, the best that they can be. It is this normality, I realise, this cherished mateship and the lightness and laughter of it all, that I miss most.

Meanwhile, back in Zimbabwe, the ramifications of ‘the spy letter’ are still being dealt with. One afternoon, while relaxing in my childhood home, I receive a phone call from the Australian Embassy in Harare. ‘We recommend that you consider not returning to Zimbabwe,’ says the voice on the end of the line. It is what they have to say. I appreciate their concern and promise to think about it.

I also receive other advice. My contacts in Harare assure me that ‘the abuses of the past will cease’. But I’ve had many such assurances over the past 28 months since the ex-governor first laid claim to Kanondo and Khatshana.

It would certainly be easier, safer, not to go back. Yet the more the land claimants and the hunters push, the more I’m determined to stay on and continue my work with the elephants.

My parents, approaching their mid seventies, say to me, ‘If you feel good where you are, then so do we.’

I’m actually unsure how good I feel about it all. In fact I feel more exhausted than I ever have. But the pull of Africa, the yearning for this other less-routine life, is still ridiculously strong. The enormous Australian sky, the great Aussie outdoors, the reassuring pulse of a safe, secure life, is not enough to hold me here. I return to Zimbabwe, hurled back to this frightfully different existence, with ar

mfuls of goodies in my suitcase—as if that might help me to cope. It doesn’t, of course.

With new personnel in the local Parks Authority office, the ex-governor’s family decide to try their luck, and reapply to hunt on the land sandwiched between the two photographic lodges on the vlei. The fact that the Parks Authority actually investigates the feasibility of reissuing a quota, in total disregard for Minister Francis Nhema’s previous directive banning them from ever hunting there again, is further evidence of corruption and collusion.

Nothing has changed. It never does.

AN EAGLE IN THE WIND

2006

‘You need to get your smile back,’ observes an anti-poaching colleague as we stand together in my garden, amid beds of succulents and colourful bougainvillea that I’ve planted and tended lovingly. He is right.

Although the ex-governor and his family appear to have disappeared from my day-to-day life, it frequently seems like there’s little left to laugh about. I once read that the average four year old laughs 300 times a day. The average 40 year old, having battled through a few decades of life, laughs only four times a day. How sad is that? The average 40-something year old living in Zimbabwe has even less to laugh about.

I resolve to get my smile, and my laughter, back.

One thing that does frequently make me smile is the ten sausage trees growing in my little garden. It took a few years for them to appear but the phallic sausage shapes I brought back from the roadside during my Mana Pools trip have propagated alarmingly well, without any help from me. I gaze at them now, wondering if I’ll be here to see them produce stunning flowers and fruit.

Something else that does make me smile is that I’ve managed to write and release a second book. (I think everyone should live without television, radio, newspapers and internet for a while and rediscover squandered time!) It’s another self-published, Zimbabwe-only edition; my diary of 2005 together with a record of the changing months and seasons, which I’ve named A Year Less Ordinary.

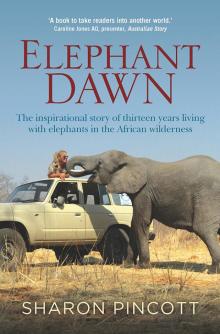

Elephant Dawn

Elephant Dawn