- Home

- Sharon Pincott

Elephant Dawn Page 14

Elephant Dawn Read online

Page 14

The loud thud of something hitting my bonnet startles me and I look up in alarm.

‘What the—?’ I gasp in sheer terror.

There, covering more than the length of the bonnet, its body in a curl, is a horribly long, mottled, greenish snake. With its head held aloft, very close to my wipers now, it’s about to slither up and over my windscreen.

I shout and swear and bang on the glass of the windscreen to try to scare it away. My other hand is already opening my door, preparing an escape route. I frantically bang some more. The snake turns and slides off the bonnet.

I jump out, terrified that it might now be coiled somewhere underneath my 4x4, but I can’t find any sign of it. I stand there for a few minutes, hugging myself and looking around anxiously, hoping to catch a glimpse of where it has gone.

What sort of snake was that? My heart is still pounding. Boomslangs are that colour, and are known to prey on birds’ eggs and fledglings. And they are deadly!

I am totally freaked out.

I eventually climb back into the driver’s seat, look high above my head and shudder. If that snake had fallen just one metre further back, it would have landed right on top of me, through my open roof!

How long had that slithering reptile been up there, hovering above me in those branches?

I determine never to park under that tree, or perhaps any tree, ever again. Death by sunstroke is preferable to death by snake, I decide.

‘Death by the governor would be worse,’ Shaynie says to me, after I tell her this story.

We do not laugh.

The reappearance of some of the governor’s men makes me extremely uneasy. It’s very clear that they believe themselves to be above the law. I’m so tired of their ongoing harassment and verbal abuse. I report them again, directly to Harare.

One week later, official notification is received at last. The governor’s family have been ordered to vacate. Tourist game-drives and anti-poaching patrols will soon be able to recommence.

‘Do you believe it?’ Shaynie asks.

‘It’s been almost sixteen months since they claimed this land. If it doesn’t happen this time,’ I say, ‘it never will.’

During this period, I’d discovered powers of resilience that I didn’t know I had. However, the situation is now unendurable. Either they’re really gone this time—or I need to be. I’m assured by the policemen, still based on the estate, that they’re really gone for good this time.

‘So why then are you still here?’ I ask them, searching for reassurance.

‘We are just waiting for orders to leave,’ they tell me.

And then, suddenly, one of them who has only recently arrived is jumping around, pointing with excitement, a huge smile on his face.

‘Arrhhh, arrhhh. He is too big. It is my first time to see one,’ he says with astonishment, staring at an approaching elephant. ‘Arrhhh. He is too big,’ he repeats, again and again.

To the Shona people he is Mhukahuru, the hugest animal of them all.

Another of the policemen looks deep into my eyes and says: ‘One day, Mandlo, the elephants will speak to you, but only to you. It will be a miracle.’

‘But they do already speak to me, in their own unique way,’ I say with a smile.

‘Arrhhh but no. They will speak to you with our words, Mandlo. A real miracle it will be, just for you.’

He is trying to give me hope, I think; trying to give me something to look forward to. ‘I will be sure to listen closely,’ I say. There are, after all, plenty of little miracles happening all of the time in the Hwange bush.

There are indeed heart-warming miracles like this one, which I witness a little while later.

There’s one male bushbuck that I see regularly when in the field, always at the same pan. His ears are a little tattered, his horns worn, and the hair on the back of his neck is balding, but he is a handsome gentleman nonetheless.

I’m sitting in my 4x4, door open, watching this buck while he nibbles on tasty leaves about twenty metres away. He seems so peaceful; I can’t bring myself to start my noisy engine and move off. I have no wish to frighten him. Instead, I watch some more. He drinks and browses and then stands quietly in the shade of a bush, having covered his horns with mud.

Then, he walks straight towards my vehicle and puts his nose to the petrol tank. He moves slowly towards me, my legs dangling out of my open door. He comes closer and closer and I wonder, bewildered, if he is perhaps blind or deaf. Now no more than an astonishing twenty centimetres away from my knee, he puts his head down and sniffs the elephant identification folders that are on the floor behind my seat. Then retracting his head just a little, he gazes up into my eyes. His own trusting eyes are huge liquid pools.

I hold my breath and dare not move even my eyelids. He is definitely not blind. He looks particularly old and wise. Slowly, I move a finger towards him, unbelievably close to his handsome face. He twitches his moist nose, but still does not move. I sit awestruck.

I remember the camera on my lap, already knowing that he’s too close to photograph even his eye. It’s a terrible habit, this overwhelming urge to photograph everything. He stays next to my leg as I very slowly put the camera to my face. I know that it won’t focus, but the photographer in me has to try. He jumps back, startled by the noise of this strange machine. Yet still he stays close by.

Eventually, he moves off slowly into the bush while I sit mesmerised by what has just happened, my heart pounding.

And for a moment I believe it. Nothing bad lasts forever.

WILL THE EAGLES LOOK OUT FOR ME?

2005

There is always life and death on the African plains. New births bring great joy. Elephants give birth roughly every three and a half to four years on average, and so most adult females have by now given birth in the years that I’ve been in Hwange. Some births, though, are infinitely more exciting than others.

When I see my elephant friends wandering with just their youngest calf in tow, as they do when they’re in oestrus, or when I occasionally see them actually being mated, I note the dates with excited anticipation, knowing that 22 months later there will likely be a new little bundle of joy. Sightings of all of the families reduced significantly during the land take-overs however, with months sometimes passing before I would see a particular family again, putting a big hole in my data collection. I do know, though, that Lady is due to give birth.

It is late March when I finally come upon the L family again, at Kanondo. I’m so relieved to see them all happily together now that the governor’s family is gone, and I look expectantly for the tiny baby that I think might be among them. But the baby is still in Lady’s belly, I can see that for certain. She is huge, her breasts—which are very human-like and visible between her front legs—are enormous.

I pull up just a metre from her while she continues, on her knees, to use her tusks to break away large chunks of minerals. In her heavily pregnant state she can’t get enough of them. Clearly, pregnancy cravings are not limited to humankind. Lady has not seen me for three long months, and she is completely ignoring me.

I am indignant!

‘Lady, you don’t even want to say hello to me?’ I ask her, shaking my head. ‘I am hurt. You need to rethink your priorities,’ I tease her.

Actually, I am secretly honoured that a wild elephant can ignore my close presence so totally. After several long minutes, having had her fill of natural minerals, Lady snakes her trunk inside the window of my 4x4 and gives me a friendly throaty rumble. I’m tempted to ignore her! Of course, there’s no chance of me being able to do that.

‘Finally!’ I exclaim, my hand rubbing her trunk. ‘You wicked woman. You’ve got a baby in your belly,’ I tell her.

She shakes her huge head in response, ears flapping like sails in the wind, as if to say, ‘I’ve been carrying this 120 kilogram burden for 22 long months. Don’t you think I know that?’

She must surely give birth any day.

Two weeks

later I’m cursing a flat tyre that has delayed me while following a mating pair. With other elephants only a few metres away, I crawl around in deep sand—keeping as close an eye on them as they keep on me—and manage to change the tyre, but not before the oestrous female has wandered off. Covered in sand and grease, I drive on, filthy and frustrated.

Then, I come upon something so much better, and immediately feel extremely grateful for the delay. It is Lady—and she has a tiny baby girl in tow.

I’m as thrilled as any surrogate mother would be! Lady brings her newborn right up to my 4x4, the little one oblivious to this metal monster before her, and suddenly there is a tiny trunk pressed up against my door.

‘Look at your baby! You’ve got a baby,’ I croon to Lady, over and over again.

This is the most adorable elephant calf I’ve ever seen—although for sure I am more than a little biased. She is still bright pink behind the ears, with bright blue eyes. Led astray by her two five-month-old cousins, Litchis and Laurie, and ten days old at most, she leaves her mother’s side to fool around with them. She’s unusually adventurous for such a young elephant and Lady makes no attempt to curtail her wanderings. Beside her mother’s huge form, she looks like a tiny doll, no bigger than Lady’s ears. The whites of her eyes are, unusually, very prominent, giving her a permanently ‘surprised’ look. The soles of her feet are a very pale pink.

She is wonderful.

To repay my friend Carol for her thoughtfulness and generosity towards me and my work, I give her the privilege of naming this gorgeous little baby. She agonises over this task for many days, umming and ahhing and deliberating, and further tossing and turning in her bed. She imagines me, out in the field, crooning to this young elephant, and wants her name to be special.

Carol eventually names her Liberté; Libby for short. It is an undisguised plea for freedom, equality and sanity in this troubled country. For now, there is indeed more trouble.

The Ruling Party has initiated what has been dubbed ‘Operation Murambatsvina’, which means ‘Drive the rubbish out’. Hundreds of thousands of people across the country have had the only city homes they’ve ever known, and their vending stalls, demolished by bulldozers. These have suddenly been deemed illegal slums. Throngs of desperately poor unemployed people, trying to find a way to feed themselves, are homeless and distraught, left with nothing but a couple of items salvaged from the rubble. The Opposition describes it as a heartless and ruthless campaign to drive out a large chunk of those city-dwellers who voted overwhelmingly against President Mugabe’s regime in the March parliamentary election. This election was widely reported to have been marred by intimidation, threats and electoral fraud. Amnesty International declared it not free and fair. There is outrage around the world over this latest violation of human rights and the government’s indifference to the suffering of its own people. Once again, I’m pleased to be in the bush with the wildlife, trying to concentrate on other things.

But revenge now permeates the bush too. In Zimbabwe, if you dare to stand up to the unethical and unscrupulous, you will pay the consequences. And so what happens to me next is no real surprise.

The governor’s family are gone from Kanondo and Khatshana, but they’re still in the area of the Presidential Elephants. During his time as governor, this man allocated yet another prime piece of land to his family: a small strip on the vlei, sandwiched between two photographic safari lodges, that he placed in the hands of his son and brother-in-law. Despite this land being right in the middle of two tourist lodges, they’d managed to secure a quota to hunt for sport here as well. So, these men are still in the vicinity and causing ongoing problems. Together with other concerned people, I’ve been urging for this third hunting quota of theirs to be withdrawn.

In the meantime, they have continued to hunt, driving their private vehicles (and hunting vehicles with international clients) up and down the vlei among tourists who’ve come to see live animals, not dead ones. The very last thing that any photographic tourist wants to see is hunters, guns and slaughtered animals.

When I see the governor’s son once again driving towards the gate to the tourist vlei, I approach him on foot. I force myself to greet him, and then remind him, as politely as I can, that these are private roads, which he has no approval to use. I suggest that he park his vehicle and go and speak to the general manager of the lodge, who has overall control of them, and whom I know would like to speak to him.

Already angry that his family lost Kanondo and Khatshana (land that was, clearly, never theirs to lose), and holding me primarily responsible for it, he responds by thrusting his arm through his open window, and punching me forcefully under my chin.

I am lucky that he is sitting lower than I am standing. If we’d been at the same level, I would have borne the full brunt of his punch in the middle of my face. The incident leaves me shaken, but not seriously hurt. By now I expect no less of this family.

When I report this incident to the police and then to my Harare contacts, I receive a phone call from a high-level police commander in Harare encouraging me to prosecute.

‘Do not get involved with these people,’ Shaynie cautions me. ‘Which of them can you trust?’

‘You want me to sit back and let these thugs physically attack me?’ I ask, knowing that Shaynie would never agree to that.

‘Just be very careful,’ she urges, determined now to stay in daily contact in case I disappear. It’s a phrase you hear regularly here: that someone has ‘been disappeared’, in a similar way as you would say someone has ‘been murdered’. Those who have ‘been disappeared’ occasionally turn up again, the worse for wear, but not often. Their bodies are usually never found.

I agree to prosecute, in the belief that somebody has to start standing up to these politically connected men. Then I get cold feet, and withdraw my case. But the police and some members of the (usually dreaded) CIO convince me once more to proceed, so that there’s a public record of what is happening in these wildlife areas. These organisations, which once sent emissaries to intimidate me, now appear to be my allies. This is the way of Zimbabwe. You simply never really know whose side anyone is on, which makes things even more scary.

I’ve never been to court before, let alone in Zimbabwe. I arrive under police escort to ensure that I make it safely. There are people everywhere.

Both the waiting area and the courtrooms are spartan and chilly. Perhaps for my benefit, the proceedings are in English. I’m asked to give my version of events. To my surprise the magistrate is writing everything down, in longhand, on a sheet of white paper. I slow my words, and finish my account. I am not cross-examined. My witnesses give their accounts next. Then it’s the turn of the accused. He does himself no favours, initially denying that he assaulted me, and then constantly contradicting himself, his story making little sense.

Unusually perhaps—in a country where political intimidation is not uncommon—the magistrate takes no account of the accused’s family connections and justice prevails. The court system in Zimbabwe works strangely, however. The convicted get to choose their own punishment. My assailant is asked to choose between community service, a fine, or jail. Naturally, with plenty of money at his disposal, he chooses to pay a fine. But, once again, he’s in front of the wrong magistrate.

‘You are too rich,’ says the magistrate. ‘A fine will not hurt you. You will learn nothing from a fine.’

So, the son of a cabinet minister (no longer a mere governor following the recent election) is sentenced to 40 hours of community service, cleaning in a clinic. I imagine that he’s never cleaned anything in his life. The black African spectators in the courtroom are perhaps thinking a similar thing, since murmurs and chuckles fill the air. I sit quietly.

‘Now there’s really going to be trouble,’ is all that Shaynie can say to me when I later relate these proceedings to her.

Words from Karen Blixen’s book, Out of Africa, subsequently play over and over in my mind: ‘If I know a song of

Africa . . . does Africa know a song of me? . . . would the eagles of Ngong look out for me?’

Will Hwange’s bateleur eagles keep looking out for me?

It doesn’t end there of course. When the family’s sport-hunting quota for the piece of land between the two photographic lodges on the vlei looks likely to be withdrawn by Minister Francis Nhema, a so-called ‘professional hunter’ (that is, a Zimbabwe-based hunter who accompanies foreign paying clients) arrives to confront me, practising his art of intimidation. He’s a man with a dubious reputation.

‘You are causing us too much trouble. Do you understand?’ Headman Sibanda spits at me, his face mere centimetres from mine. Too angry to care, Sibanda has cornered me at one of the big photographic lodges so there are many witnesses to his threats.

Mustering all of my self-control, I tell him calmly that he is speaking to the wrong person; that I will go and find the general manager of the lodge for him. But he isn’t interested in speaking to anybody else.

‘You’re just a fucking white. Fucking white trash,’ he lashes out.

I look him in the eye and slowly raise an eyebrow. Is that the best you can come up with? I think to myself.

I’ve had enough. I move to walk away but he herds me, just like I’d recently been herding a snared buffalo, and uses his shoulder to impede my free movement. He’s obviously aware of the recent court case, since he is one of the ex-governor’s hunters, and knows not to actually touch me. I shake my head, and eventually manage to get my body away from his. He climbs back into his vehicle, while I immediately report the incident to people I trust.

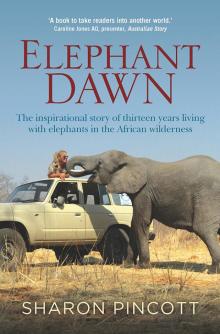

Elephant Dawn

Elephant Dawn