- Home

- Sharon Pincott

Elephant Dawn Page 12

Elephant Dawn Read online

Page 12

And then there is more tragedy on the estate.

At Kanondo, Whole comes to me when I call to her. She seems more eager than ever to say hello. I’m crooning to her as she stands beside the door of my 4x4, looking forlorn, when I’m distracted by an awful gasping sound. I look around and spot her three-year-old son, Wholesome, nearby. He has a snare wrapped tightly around his little head and neck.

‘Oh please. I just can’t bear this anymore,’ I blurt aloud to no one.

Wholesome is gasping for breath and I realise that his windpipe must be partially severed by the strangling wire. I know that I’m too late, but I fumble with my radio and try to organise urgent assistance regardless. Wholesome dies in front of my eyes some 30 minutes later, before help can reach us.

I’ve known Wholesome since he was just days old.

Whole races to him when he falls, as does his sister Whosit. They both use their trunk and tusks in a frantic effort to lift him and hold him upright. It is the most heartbreaking scene I have ever witnessed in my life. Other family members race to assist as well, and with so many elephants now trying to help, Wholesome’s little lifeless body ends up being pushed into the waterhole.

I shake myself out of my own grief, and realise that I should be video-taping this event. But how does one do that at a time like this? It seems heartless, but I force myself to pick up my video camera.

Mother Whole, sister Whosit and grandmother Wendy remain close by the little elephant who has been such an important part of their lives. They wander right into the water and stand by his side, constantly touching his lifeless body. Occasionally, they try again to lift him. Later, after Wendy moves off, Whole and Whosit return to his carcass again—and again and again. They move off, sometimes as far as 25 metres away, and then race back to his lifeless body. Even though several hours have passed by now, they continue to do this over and over again.

Eventually, Whole comes and stands by the door of my 4x4. The way she holds her head, her mouth, her eyes; everything about her spells intense grief. Whosit resolutely refuses to leave her dead brother, even when all other family members have wandered a short distance off into the bush. My heart aches for them all.

Tuskless Debbie and Delight and others from the D family later pass by, spending eerily quiet time beside Wholesome’s body, paying their respects. By now it is dark, and I drive home dejectedly.

Spoor around Wholesome’s body the next morning confirms that many elephants have visited him during the night. The governor’s family then butcher Wholesome’s little body, taking his hide, his ears, his tail and the meat—for sale. Humans had killed him, and humans then greedily took all that they could, for profit.

Elephants have a sense of death like few other animals. They will walk straight past the remains of another animal, but they’ll always stop at the new remains of one of their own kind. Family, extended family and clan members stop frequently at Wholesome’s butchered carcass, touching it gently with their trunks. It is Anne and Andrea, and others from the A family, now spending extended time beside his remains. They silently back into their dead companion, and slowly move a hind foot in a circling motion over the carcass in a chilling gesture of awareness.

As I watch them, moved and saddened, I vow that Wholesome’s death will not be in vain. He will help to highlight the plight of the remaining Presidential Elephants.

This time, I choose to ignore the orders of Wildlife Minister, Francis Nhema, to not speak publicly of snaring. How can we possibly fix the snaring problem if the officials refuse to acknowledge it exists? How can we get assistance with expensive immobilisation drugs, antibiotics, dart guns, anti-poaching unit supplies and the like if we can’t show people what is happening here?

I send around graphic photographs and the story of Wholesome’s death. I mention the land grabs, although I don’t name the governor or his family. I don’t send these to the press, but somehow they end up there. Without my knowledge or approval, one of the tightly controlled government newspapers publishes the story. Obviously it hasn’t done its homework, and doesn’t actually know who these land grabbers are, since stories are never published that are disparaging to those in power.

Needless to say, the governor is not pleased. In fact, the governor is furious. I am immediately banned from the land again. He targets me as the person he needs to get rid of if he and his family are to keep this land.

Suddenly I have the police, from the nearby township of Dete, searching for me, asking endless questions and demanding to see my passport and my permits. The governor is using his considerable political weight to try to have me expelled from the country. Clearly I am now persona non grata. If I had been a local, I would likely have been thrown in jail by now or have simply disappeared. Being a foreigner affords me some small measure of safety.

I think about the white Zimbabwean journalist and esteemed author, Peter Godwin, who dared to investigate and report internationally on something much worse, the Matabeleland Massacres, including firsthand accounts of bodies being dumped down abandoned mine shafts under cover of darkness. He was forced to flee his own country, hurriedly boarding a flight out from Harare after a tip-off that he was about to be arrested for doing so and thrown into the notoriously awful Chikurubi maximum security prison, where overcrowding and disease is rife. He was warned he would languish there for years. Shortly afterwards, Peter was declared an enemy of the state by the ZANU-PF government. ‘Persona non grata in my own home,’ he later wrote of himself.

‘Sharon, get out of there,’ Shaynie emails to me, knowing exactly what her government is capable of. ‘And if you don’t, I’ll come and kidnap you myself,’ she threatens.

‘Shaynie,’ I say, ‘you know that I have to stay.’

Out in the field I battle with thornbush roadblocks erected to deter me, and regular shouts of abuse. One unidentified man runs after my 4x4, waving an axe. This is the most frightening time that I have faced in Zimbabwe to date. I know all about threats and intimidation in Africa. I never expected, though, to be on the receiving end of them.

Yet the more they want me gone, the more I become determined to stay. I carry on as best I can.

I come upon Andrea the elephant, with her immediate family in tow, and email a photo of them to my friend Andrea in New Zealand. A reply drifts back across the ocean. After deciding firstly that ‘she’ is a good-looking elephant, Andrea declares ‘if you look between my legs I’ve got great breasts!’ And then, making a comparison to her own, she adds: ‘Not that they should really be between my legs but it’s a major size improvement on what I have now!’

I’m grateful for friends who make me smile.

Carol, her friend Lynn, and a group of their friends arrive from Harare out of the blue one morning, and this brings another smile to my face. They’re heading to a lodge inside the national park for a few nights of rest and relaxation.

‘You’re coming with us,’ Carol declares, immediately sensing the anxiety behind my smile.

‘But . . .’

‘There are no buts,’ Carol says, in a voice that invites no discussion. ‘You’re coming with us,’ she repeats. ‘Grab some clothes. You need to be away from here.’

Soon we are all heading to an upmarket safari camp called The Hide, close to where Andy is buried. It is far enough away to be peaceful. It’s Carol’s great pleasure to spoil her friends, and I am exceedingly grateful for this thoughtful gesture.

It is certainly enjoyable to play tourist, when you can very easily pretend that nothing horrible is going on behind the scenes. Tourists rarely see evidence of any of it. A third bed is placed in Carol and Lynn’s large luxury tent, and I hope that I won’t disturb them with another restless night’s sleep. My dreams have turned dark and disturbing.

My dream on this particular night is peculiar and unusually vivid: I am a passenger in an open game-drive vehicle. We hit a bump and I go sailing up into the air, higher and higher, while the vehicle continues on its way. Carol quickl

y realises that I am no longer in the vehicle and looks around frantically trying to find me. There I am, floating high in the sky, strangely suspended in the cool air above. The guide reverses at speed to try and catch me before I plummet to earth. I don’t plunge to the ground however. Instead, I sail gently back down through the clear air and land, unharmed, precisely where I’d been seated beforehand.

I awake in a fit of uncontrollable laughter. Fearing that I’ll wake my room-mates, I bury my head beneath my pillow. For some reason though, I can’t stop the laughter that’s so intense it leaves me gasping for breath.

Early the next morning I tell my friends about my dream.

‘I heard you,’ says Carol.

‘Me too,’ says Lynn.

‘I thought you were sobbing, needing to rid yourself of all of the tragedy that’s been going on,’ Carol says softly. ‘So I left you alone. I’m so pleased to hear that you were actually laughing!’

We laze on our beds, analysing my dream and speculating about its meaning. We finally conclude that I’m on a bumpy journey, experiencing things totally alien to a normal way of life, but everything will be okay in the end.

I love how my friends tell me what I need to hear.

SKIDDING SIDEWAYS

2004

The police are waiting for me on my return.

The governor and his family have nothing on me. My permits are in order. It is intimidation, pure and simple.

At one stage I’m advised by a concerned colleague to leave the country, if only temporarily. I think this surely isn’t necessary, but after listening to what he’s heard from others in the know, I decide that perhaps I should. I start throwing clothes and toiletries into a bag.

Soon afterwards I receive more frantic advice: ‘You may not make it to the airport. Stay where you are.’ He’s worried that I might meet with an ‘accident’; that I might get run off the road. It’s something that used to happen in the post-war period. ‘Death by puma,’ it was called back then, after the heavy army trucks called pumas.

I think people’s imaginations are getting the better of them, but I can’t be certain. They’ve lived in this country far longer than I have, and know better than me what some are capable of. Suspicious ‘accidents’ are still very much the norm. Blowouts are all too common. When a marked car goes in for service, a bullet from a heavy calibre rifle is placed in one of the tyres. When the vehicle travels at high speed the bullet generally gets hot enough to go off, causing the vehicle to spin out of control.

‘Never be at your rondavel on a Friday afternoon,’ I’m warned by another person with first-hand knowledge of what can happen. ‘If they lock you up then, you will spend the entire weekend in jail. And you don’t want to spend that long in a Zimbabwean jail.’

All of this is not just bewildering to me. It is shocking. I haven’t done anything wrong. In fact I’m the one—and one of the very few right now, it seems to me—trying to do the right thing by the wildlife. But this is Zimbabwe. It does not matter.

I’ve somehow found myself embroiled in games that I have no stomach for, struggling against powerful adversaries. It is something that I never bargained on or sought out. I imagine my body floating in a pan, chewed on by crocodiles, my death somehow having been made to look like a careless accident on my part. I warn my friends, rather than worry my family: ‘If something like this ever happens, don’t you believe it’.

I alert the Australian Embassy in Harare to my situation, feeling better just knowing that more people are at least aware. The embassy makes it clear to me, however, that other than providing a list of lawyers and making sure I have food, they can do little to help if I’m thrown in jail.

All of this is draining away my spirit and my zest for the elephants. I long for things to be as they were when I first arrived. There are awful days now when I can no longer see beauty in anything.

‘Did you really think that it would stay as it was?’ a friend asks me one evening.

‘I thought it might . . .’ I whisper sadly.

The Kanondo and Khatshana of sanity and peace. They have disappeared before my very eyes.

My days of innocent enchantment are long gone too but the nights are the worst, increasingly filled with torrid dreams. It is at night that I hear most of the spine-chilling shots. And I feel an unspeakable despair. I close my eyes and weep in grief and frustration at what is going on around me.

I no longer like to get to know any of the big-tusked elephant bulls well. Sooner or later they disappear, leaving only those with small or broken tusks to roam the estate. These days I’m always relieved to see broken tusks, making these elephants less attractive to the sport-hunters and the poachers.

I remain disheartened that so few people in the area are speaking out. Sometimes it’s as if there’s an echoless void out there. Australia seems so far away. I know that I could be there. But my elephants in Australia are only statues made of stone. I am dogged in my determination to stay, for the sake of the animals that I’ve grown to love. The most dangerous predator in Africa, I’ve come to realise, is not the lion. Nor can the hippo, the buffalo or the elephant hope to compete. The most dangerous animal by far is man.

Hwange once seemed so seductive, so serene and largely untouched. Now I’m constantly alert. I’ve ceased to harbour even the slightest romantic notion of the Zimbabwean bush. I muster my resolve, and continue on. But the harassment continues.

Gunfire is now out of control. The elephants are moving in large aggregations, probably for safety’s sake. One minute there are no elephants in sight and the next scores of them are racing, terrified, out from the tree line. Today there are several families fleeing in tight formation, with ears flat and tails out. One of them is Whole’s.

It takes me hours to find the W family again after this distressing episode, and another two hours to regain just a little of their confidence. It is Willa who comes close to my vehicle before the others. She approaches hesitantly, while I alternate between singing ‘Amazing Grace’ and talking gently to her (something that I do frequently now, especially after distressing episodes), reassuring her that everything is alright. Just as most family members are beginning to settle, a game-drive vehicle approaches and the elephants take off into the bush yet again at speed, and in complete silence. Now they’re frightened of a game-drive vehicle—specifically this particular vehicle.

When I find the W family again the next day, I spend the entire morning with them—attempting to rebuild what has been broken.

Soon after, six officials arrive at a nearby lodge and demand to see me. Some are from the Immigration Department and others are believed to be from the dreaded CIO—the Ruling Party’s Central Intelligence Organisation, or secret police, feared for its brutality. They have travelled all of the way from Harare, on the other side of the country, to talk to me. They’re no doubt acting on instruction from the governor. Although the CIO has a reputation for harassment and provoking fear, all six people leave quietly after a short and trouble-free meeting. I am feeling rattled however. I can only hope that I’ve convinced them that I have nothing to hide.

Still, I now feel that I have no choice but to escalate all of this to a higher level. I travel to Harare, to the offices of three different Cabinet ministers. This is a little daunting, since these men are practically worshipped by the masses. They get around like mini-gods, with their own state security details.

I meet first with the Wildlife Minister, Francis Nhema. Having previously signed the governor’s sport-hunting quota, he does little to boost my confidence. He won’t look me in the eyes. During our meeting he speaks vaguely, and so softly that I have to strain to hear him. His eyes burn into my chest. I have no idea what to make of him. All I know is that he has done little to save the wildlife under his watch. If nothing else, I suppose, at least I have met him. I’m left with the impression that he’s unlikely to follow through on anything, unless specifically instructed to by the President’s Office. His distant and dr

y style unsettles me.

I next meet one of President Mugabe’s closest advisers, one of the most powerful and feared men in the country; the minister responsible for state security (which includes the CIO), and for the land reform program.

‘Don’t be afraid,’ Minister Didymus Mutasa says to me, holding my hand within both of his and looking me in the eyes.

‘I’m not afraid,’ I lie. I’m aware that Minister Mutasa, like Minister Nhema, must know the governor very well. They’re all colleagues after all. Clearly he believes that there is good reason for me to be afraid.

‘Your work is crucial. It must be allowed to continue,’ Minister Mutasa says to me.

I am fully aware of this man’s reputation. I know that he could have me taken out just as quickly as he could arrange for my protection. But having been involved in the original Presidential Decree years earlier, he appears to have retained some interest in these elephants and my gut tells me that he’ll be a useful ally.

Then I meet with the Immigration Minister to try to find out what’s holding up my work permit renewal. His face registers something close to shock that I’m asking to be allowed to stay in this troubled country. He spends most of our meeting lamenting the fact that he’s struggling to pay for the education of his children.

I leave Harare with increased confidence that my permit will be renewed and that the governor and his family will be evicted. I also believe that I have the support of at least one very powerful man. I’ll need this if I am to survive here. I’ve been assured that I have the support of the Wildlife Minister too, although I’m still not convinced about this. I find it difficult to trust somebody who doesn’t look me in the eyes.

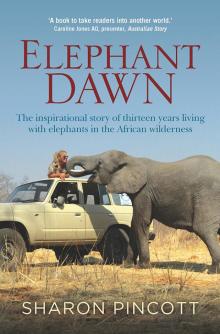

Elephant Dawn

Elephant Dawn